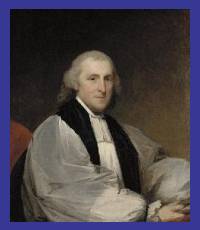

William White was born in Philadelphia in 1747, went to

England in 1770 to be ordained deacon and priest, returned in 1772 and

became first an assistant and then the rector of the Church of Christ

and Saint Peter in Philadelphia.

He served as Chaplain of the Continental Congress from 1777 to 1789, and

then as Chaplain of the Senate. Before the American Revolution, there

were no bishops in the colonies (partly because the British government

was reluctant to give the colonies the kind of autonomy that this would

have implied, and partly because many of the colonists were violently

opposed to their presence).

After the Revolution, the establishment of an American episcopate became

imperative. Samuel Seabury

was the first American to be consecrated, in Scotland in 1784. After

action by the English Parliament permitting foreign bishops to

consecrated without taking the oath of allegiance to the King, William

White and Samuel Provoost, having been elected to bishops of

Pennsylvania and New York respectively, sailed to England and were

consecrated bishops on 14 February 1787 by the Archbishop of Canterbury,

the Archbishop of York, the Bishop of Bath and Wells, and the Bishop of

Peterborough.

White was largely responsible for the Constitution of the Protestant

Episcopal Church in the United States of America. At his suggestion, the

system of church government was established more or less as we have it

today. White was insistent that lay leaders take a role in shaping the

life and policy of the Episcopal Church.

He was prepared to have a Church without bishops, but when English law

made bishops in the newly created nation possible, he worked ardently to

bring unity and coherence to the Episcopal Church.

He bridged the gap between the claims and concerns of the clergy of New

England, especially Bishop Seabury, and his friend and colleague, Bishop

Provoost. White was regarded as “a saint, a scholar, and a statesman.”

See his “Case for the Episcopal

Church”.

William White