II. The Church reaches out to Judea, Samaria and beyond (Part 2)

Luke summarizes up to this point: 9.31.

The Church is being “built up” -- edified; literally the term in Greek means the “household is growing.”

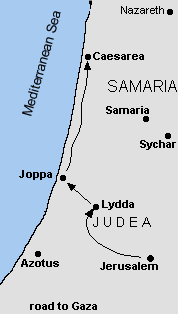

This growth is taking place “throughout” Judea and Samaria -- Luke has given us some insight into these places; AND in Galilee -- he has not mentioned anything about this area so far. Apparently, he possessed no direct information about Galilee.

The Church’s life was characterized by:

- walking in the fear of the Lord -- reverence and wonder at God’s presence;

- “comfort of the Holy Spirit” -- the practical effects of the

presence of the Spirit could be seen in the lives of the community; this

term helps us understand more of Luke’s theology concerning the Holy

Spirit.

Luke now takes us back in time once again. He is going to show us another

turn of events that resulted from the persecution of Stephen.

9.32-10:48: The Gentiles receive the Holy Spirit

Peter and John returned to Jerusalem after their inspection tour (8.25). Sometime after this, Peter -- fascinated by his experience among new the new communities --began to travel more extensively on his own. (No indication is given that new troubles arose, or that his trips were authorized by the Jerusalem community.)

Peter comes to three cities: Lydda, Joppa, and Caesarea.

At Lydda, Peter found a Christian community. In it, was a man named Aeneas who had been bedridden for 8 years with paralysis. Peter heals the man, and this news brought still more converts into the church. (Note that Aeneas must already have been a Christian: following his healing, he is not baptized, as is the case in such events elsewhere.)

Peter next goes to Joppa (9.36 ff.). Here a disciple named Tabitha suddenly dies during Peter’s visit. (She is described as “full of good works and acts of charity.”) Her nickname was “Gazelle” -- clearly a vivacious, active woman. The death profoundly grieved the Christian community. Peter raises the woman from death -- a result of prayer, according to Luke. Great joy fills the community, and more converts are added to the Church.

Caesarea

was a man made harbor on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. There was no

"natural" harbor along the coast. Herod built this harbor, a work of

considerable engineering ingenuity, as a gesture to the Emperor.

Caesarea

was a man made harbor on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. There was no

"natural" harbor along the coast. Herod built this harbor, a work of

considerable engineering ingenuity, as a gesture to the Emperor.

This is a reconstruction of what the harbor may have looked like. Herod's

palace is seen at the center top. A temple dedicated to the Emperor is at

the center left part of the picture.

Luke’s real interest centers on Peter and Caesarea.

Peter was staying on in Joppa (9.43).

Cornelius, a Roman centurion living in Caesarea (a port

town, fed by a remarkable aqueduct seen at left), has a vision. He is described as a God-fearer -- that is, a Gentile

attracted to the Jewish faith. Cornelius was highly regarded for his

devotion and his generosity. In the vision, Cornelius is directed to send

for Peter. Cornelius sent his servants, and a soldier (for protection) to

fetch Peter --a journey of about a day and a half.

Cornelius, a Roman centurion living in Caesarea (a port

town, fed by a remarkable aqueduct seen at left), has a vision. He is described as a God-fearer -- that is, a Gentile

attracted to the Jewish faith. Cornelius was highly regarded for his

devotion and his generosity. In the vision, Cornelius is directed to send

for Peter. Cornelius sent his servants, and a soldier (for protection) to

fetch Peter --a journey of about a day and a half.

Peter has a vision as well -- but his is not as clear-cut. While he is struggling to come to terms with the vision, he becomes aware of his visitors. The Spirit gives him courage to meet the strangers (he may well have feared arrest), who relate their mission.

After a meal and a good night’s rest, Peter joins the others and sets off for Caesarea. Some of the Christians at Joppa go along as well. Cornelius had prepared for this gathering by inviting his relatives and close friends. On meeting Peter, Cornelius showed him profound respect -- but Peter reassured him that he was a common man.

Peter, now beginning to understand his dream, meets with the assembled Gentiles. At first he has qualms, but he knows this is God’s doing. Then Peter has the opportunity to present the Christian message. The “sermon” is a shorthand summary of Christian teaching -- Jesus is the Lord, the judge of a new kingdom; he brings peace and forgiveness. He was raised from the dead, the fulfillment of the prophetic hopes.

While Peter is unfolding the Christian message, “the Holy Spirit fell upon” the assembled group. What is remarkable about this is that they people were Gentiles (the Christians from Joppa were Jewish); and this outpouring of the Spirit came IN ADVANCE of baptism. Peter, realizing what was happening, asked if baptism into the Christian community could be forbidden this group. The answer, of course, was dumbfounded assent.

Peter stayed on some period of time, no doubt continuing his teaching with the fledgling Christian community at Caesarea.

It should be noted that, when the Holy Spirit comes upon Cornelius’ group, Peter is not completely sure how to deal with the results. His question is not merely rhetorical, although it draws no objection. He is submitting the question to the Christians present for their joint response.

This is apparently the first Christian community in

Caesarea. Philip, then cannot have arrived here before now.

11.1-18: The Jerusalem community affirms the work of God among Gentiles

Word travels fast. Jerusalem hears about the events in Caesarea. So, when Peter made his way back to Jerusalem, he must interpret these events to the community leadership.

The situation is complicated because Christians in Jerusalem -- called “the circumcision party” -- who see Christianity as a sub-group within Judaism, challenge Peter on his conduct: he fellowshipped with Gentiles and even ate with them! (Much less welcoming them into community)

Peter lays out the details of the events -- including his own spiritual experience. Peter is again laying his decision before a community for adjudication -- Peter is not autocratic in his actions.

The circumcision party cannot make a cogent reply -- they are “silenced.” The rest of the community rejoices in the turn of events, although in candor they may not have been entirely certain that this was good. They seem to be resigned to the fact that God “works in mysterious ways.”

It is interesting to note how Peter presents his case. In his argument,

he begins with an appeal to his own immediate experience. Then he recalls a

teaching of the Lord (11.16) to the effect that baptism in the Spirit

surpasses other ‘outward’ rites -- including presumably circumcision. Then

he appeals to the communities sense of rightness --their reason, to which is

left the final decision.

11.19-26: The Church reaches Antioch

Once again, Luke describes events that proceeded from the persecution of

Stephen. Over a long period of time, the Church was spread to places like

Phoenicia, Cyprus and Antioch. It is the latter which gets Luke’s attention

now.

Once again, Luke describes events that proceeded from the persecution of

Stephen. Over a long period of time, the Church was spread to places like

Phoenicia, Cyprus and Antioch. It is the latter which gets Luke’s attention

now.

In Antioch, something new happens. Some men of Cyrene (in Libya)and Cyprus went up to Antioch -- there were doubtless many others who went to Antioch, including Jewish Christians who originally came from that area. But these Cyrenians and Cypriotes did something totally new: THEY SELF-CONSCIOUSLY BEGAN TO APPEAL TO GREEK-SPEAKING GENTILES with the Christian message.

Of course, we have already seen sporadic efforts at proselytizing Gentiles: Philip and the eunuch; Paul in ‘Arabia’; Peter and Cornelius. But none of these were systematic efforts. All were more or less chance encounters, or as in the case of Paul, apparently unsuccessful.

The Cyrenians and the Cypriotes, apparently without authorization or other warrant, simply took it upon themselves to share their faith with Gentiles. This, in itself, is a remarkable turn of events.

Even more remarkable was the success this preaching effort had. Luke says simply, “the hand of the Lord was with them.” (11.21)

Word of this success reached Jerusalem. Now Barnabas was dispatched on behalf of the Jerusalem community to inspect this work.

Why Barnabas and not someone of the stature of Peter and John, as previously? Part of the answer must lie in the events which had ALREADY transpired in Jerusalem. We must assume that Peter had already won the approval of the community at large for his work with Cornelius and his household. That problem settled, the Jerusalem community would greet the news of the work in Antioch with more calm.

Why Barnabas in particular? First, Barnabas was a Cypriote by birth. Presumably, he could ‘speak their language’ and win their confidence. Secondly, Barnabas was known for his generosity of spirit. He was a man of reconciliation (note his role on behalf of Paul). He may even have had a deep interest in such a work, having heard of Paul’s experience with the Lord and his commission to the Gentiles.

On his arrival, Barnabas found the Church in good order in Antioch. He identified its life as a work of the grace of God, and was “glad.” Imagine his excitement at discovering that the same marks of the Christian community in Jerusalem were present and active in this alien environment!

Barnabas seems to have been well-received in Antioch. No suspicion attached to him as a representative of the Jerusalem church. This must surely be due to Barnabas’ self-understanding: he came to place himself in the SERVICE of the Church, not to exercise some kind of authority. But he nevertheless HELD authority.

The Church grew under Barnabas pastoral oversight. So successfully, in fact, that Barnabas began to look around for other help.

Barnabas traveled to Tarsus to find his old friend, Paul. What a self-confident and loving man Barnabas must have been: self-confident in that he wanted Paul’s skills and abilities to aid him; loving in that he seized this first opportunity to assist Paul with fulfilling the Lord’s commission to preach among Gentiles.

Paul accepted the post and came to Antioch to work with Barnabas. Barnabas trust in Paul was well-founded. The Church grew by leaps and bounds after his arrival.

In Antioch, the term "Christian" is first used to describe disciples of

Jesus of Nazareth (CHRISTIANOS = “little

Christ”).

-- DATELINE --

| YEAR | SEASON | EVENT |

| 36 AD | Most of year | Peter's missionary work in Lydda, Joppa, Caesarea |

| 37 AD | Early | Peter returns and reports to Jerusalem |

| 37 AD | Early | Philip arrives in Caesarea |

| 38-39 AD | A Christian community forms in Antioch | |

| 40 AD | Barnabas is dispatched to Antioch | |

| 41 AD | Barnabas goes to Tarsus to fetch Paul ti assist in Antioch |

12. 1-23

: Herod threatens the ChurchIn late 41 AD, Herod returned from Rome to Jerusalem after taking an instrumental part in the succession of the new Roman Emperor, Claudius. (For his efforts, Herod had been granted a sizable extension of his kingdom.)

As a show of power, and perhaps to ingratiate himself to the Jewish leadership, Herod seized James (Son of Zebedee), in the spring of 42. Herod had James killed, and then went after Peter. Passover caught up with him, and Peter’s execution had to be postponed. (Imagine Peter feeling like he was reliving another, earlier Passover!)

Peter miraculously escaped from prison. What happened? The whole story is related with such speed and uncertainty, even Luke perhaps did not know. Peter thought he was experiencing a dream -- and he made a very swift departure. No wonder then that various legendary elements grew up around this admittedly strange event.

The details about the visit to the house have the ring of truth, however: Peter ran immediately to the home of Mark’s mother. The disciples gathered there were praying, probably fearing the worst. Peter knocked at the door and was greeted by a maid (named Rhoda). The maid was so shocked at Peter’s presence, she immediately went in to report that Peter was standing at the door -- and the inhabitants of the house were so astounded, they stood arguing with each other over the possibility of such an event.

Peter finally got in and described what happened as far as he knew it then left instructions that James and the community be informed of his deliverance. Then Peter simply “left” -- going to “another place.” Luke does not specify where Peter went, but tradition holds that he went to Rome -- apparently to lay low until the persecution of Herod passed over. It is likely that Peter took John Mark with him.

Tradition relates that Mark, on this visit with Peter to Rome, began

taking notes on Peter’s sermons -- notes that eventually became the basis

for the Gospel attributed to him.

11.27-30; 13.1-3: The Mission of Mercy to Jerusalem

Luke sandwiches the persecution of Herod in between the account of the mission of mercy from the Antioch community to the community of Jerusalem. This gives the mistaken impression that Paul and Barnabas were in Jerusalem during the persecution.

We know from other sources, however, that in fact a famine broke out during the persecution (it may be that the persecution was prompted BY the famine -- thus ‘scapegoating’ the Christians).

During this period of time, a ‘prophet’ (preacher) from Jerusalem, named Agabus, came to Antioch. As a result of his preaching, the community at Antioch determined to send a relief fund to Jerusalem.

Such a relief fund would have been prompted by the awareness that many people -- especially Hellenistic Jewish Christians -- would have suffered in such times of shortages.

There is no indication that Agabus was officially delegated to go to Antioch -- instead, it appears that relations between Antioch and Jerusalem were completely normal, and that one of the features of normalcy was the free interchange of itinerant preachers.

Barnabas appears as the leader of the delegation. Paul is not yet a ‘star’ in his own right.

The trip to Jerusalem was for a single purpose and was obviously very quick. 13.5 indicates that John Mark had joined Barnabas and Paul on their first missionary journey. It is possible, indeed likely, that Mark had returned to Jerusalem from his travels with Peter, and -- being a cousin of Barnabas’ -- was ‘collected’ and taken along with Barnabas and Paul on the return trip to Antioch. It is pure speculation, but also likely that one of the reasons for this enlistment of Mark was that he was in possession of his notes and could relate what the preaching of Peter had accomplished after his quick flight from Herod.

Vs. 13.1 indicates that the leadership of the Antioch community was now centered in a committee of five persons: Barnabas, Simeon, Lucius, Manaen, and Saul (Paul). The names suggest a richness in the leadership of the Antioch community. Barnabas was a Cypriot. Simeon (Simon) is given the designation “Niger” -- a Roman name that derives from Cyrene. Barclay suggests that this may be the well-known figure Simon of Cyrene -- the man who bore Christ’s cross. Lucius, too, is from Cyrene. It may well be possible that Simon and Lucius were the unnamed “men of Cyprus and Cyrene” who motivated the outreach to Gentiles in Antioch. Manaen appears to have court connections, and thus be something of an aristocrat. Paul is well-known as a man of learning from a significant academic town -- one who was fluent in Greek. THUS the leadership at Antioch was a rather cosmopolitan group.

In the context of worshipping and fasting -- acts which imply an attempt to discern the will of God -- the word of the Holy Spirit came to the community: “Set apart Barnabas and Saul for the work to which I have called them.”

The community, again with prayer and fasting, lay hands on Barnabas and Saul -- an ordination -- and commission them to a missionary work.

This ordination appears to be to the “apostolate”, since Luke, without further ado refers to Paul and Barnabas as apostles (14.4). Thus we see that a community could ordain apostles:

- under the guidance of the Holy Spirit

- to engage in missionary activity (establishing churches)

It is interesting to note that the commission was non-specific: i.e., no

particular plan of action was envisaged as a part of the ordination. The

community's action was complete when the will of God was discerned and the

proper men chosen -- THEY, in turn, were free to set out their own plans.

13.4-12: Journey to Cyprus

Barnabas (he is listed first) seems to still be in charge of the delegation. He and Paul take Mark along with them. ‘They decide to make their first journey to Cyprus --apparently because it is Barnabas’ ancestral home.

They arrive in Salamis -- the major sea-port. They travel through the island, preaching in various synagogues.

Eventually they come to Paphos, the southwest end of the island. Here

they come upon a certain magus named Bar-Jesus, also known as Elymas.

Bar-Jesus is a consultant to the Proconsul, Sergius Paulus. (Proconsuls

serve at the will of the Senate, as opposed to the Emperor.) Paulus is

‘converted’ because of the ‘astonishing teaching’ of the new apostles.

13.13-14.28: From Cyprus to the Mainland

Vs. 13.13: The apostolic company leaves Cyprus and travels to Pamphylia.

Paul emerges as the leader of the delegation. This is perhaps owing to his

skill and success with Sergius Paulus. Also, from now on he will be known

simply as Paul.

Vs. 13.13: The apostolic company leaves Cyprus and travels to Pamphylia.

Paul emerges as the leader of the delegation. This is perhaps owing to his

skill and success with Sergius Paulus. Also, from now on he will be known

simply as Paul.

The company comes to Perga. Here, for reasons unknown, Mark left the company. The area is known for its malarial conditions, and Mark may well have grown afraid of this new venture. Paul, at least, regarded Mark’s return as a sign of weakness and refused to take him on subsequent trips -- this refusal became a source of contention between Paul and Barnabas.

Not much is said of the work in Perga -- obviously not much happened. The delegation then moves to higher ground -- on to Antioch in Pisidia, about 95 miles north and 3600 ft. above sea level (perhaps to get away from the conditions in Perga).

The delegation goes to the synagogue on the Sabbath and were invited to address the congregation. Paul does so. He speaks to a mixed congregation, of Jews and Gentiles who are becoming Jews (those who fear God, 13.26). Paul connects the coming of Jesus with the covenant history of the Jews, and attempts to show how Jesus is the fulfillment of the covenant promises. He proclaims the resurrection, and makes use of the empty tomb tradition. He also proclaims forgiveness and reconciliation through Jesus. Many of the congregation follow Paul and Barnabas, and form a Christian community. Paul urges them to continue in the grace of God -- so we may be sure that graces a significant concept in Paul’s letters, was already here an equally significant part of his preaching and teaching.

On the next Sabbath, Paul and Barnabas draw a very large crowd, particularly from among the Gentiles. This sparks jealousy (and fears of heresy) from the Jewish community and a sharp dispute arises between the Christians and the Jews. The result of this dispute is two-fold: Paul clearly announces a policy of going directly to Gentiles; and this announcement encourages the Gentiles to fan out to relate what they have found.

Eventually, the dissension grows so great that Paul and his company decide to leave Antioch and go on to Iconium.

Vss. 14.1 -7: A similar fate befell the apostles in Iconium: a church was established, made up of Jews and Gentiles. But Jews who refused the message stir up dissension in the community: so now there are sharp divisions in the city, some Jews and Gentiles in the Christian camp, some outside seeking to rid themselves of the pesky preachers. Fearing the heat, Paul and company leave town and go to Lystra and Derbe.

Paul and Barnabas go)on to Lystra, where they are responsible for a healing (“signs and wonders” . The Lycaonians -- people of the region -- think of Paul and Barnabas as ‘gods’ -- note that they think of Paul as the chief speaker. Paul specifically denies any power of his own, and affirms that they are human beings. Note also Paul’s idea: God was involved in the life of all men, and ‘did not leave himself without witness among any (so much for Christian exclusivism).

More disputes arose, however, and Paul barely escapes with his life. On the group goes to Derbe. But they do not leave Lystra without having formed a church (‘the disciples’).

Paul and Barnabas are able to establish a church in Derbe in relative peace.

Now the apostolic company retraces their steps through the new communities.

- On the return trip, the apostles enjoy relative peace.

- They find their churches intact, and strengthen them.

- They also appoint leaders in each community: these leaders are called "elders” (PRESBUTEROI =presbyters = priests), and are ordained (“prayer and fasting” are features of the ordination service).

Paul and Barnabas returned to Perga and tried again to preach there.

Apparently they had no greater success the second time. So. Sailing from

Attalia, they returned to Antioch in Syria and made their report. Then the

apostles stay on in Antioch, apparently resuming their leadership work

there.

-- DATELINE --

| YEAR | SEASON | EVENT |

| 41 AD | Peter imprisoned and escapes - leaves for Rome | |

| 44 AD | Herod Agrippa dies | |

| 44 AD | Mark returns to Jerusalem | |

| Peter returns to Jerusalem | ||

| 46 AD | Agabus predicts famine in Jerusalem | |

| Famine occurs in Jerusalem | ||

| 46 AD | Barnabas and Paul bring collection to Jerusalem | |

| 47 AD | Barnabas and Paul are ordained and sent off on their first missionary journey |

15.1-35: The Council At Jerusalem

In the absence of Paul and Barnabas, some Jewish Christians from Judea came to Antioch and were teaching that circumcision is binding on converts to the Christian community, in accord with the Law of Moses.

These “men” were probably of the Pharisee party-- as Paul himself had been.

They did not bear the authority of the community at Jerusalem, but were acting independently (for their own theological reasons).

The questions they were raising do not seem to have arisen in Jerusalem itself-- the Jerusalem community only becomes involved when the dispute is brought before them from the delegation from Antioch.

When Paul and Barnabas arrive in Antioch, they immediately are brought into the debate over circumcision.

Antioch appointed a delegation to go to Jerusalem and settle the issues raised by the teachers from Judea.

On their way, Paul and Barnabas have occasion to visit many Christian communities and relate their work, which all take joy in. (A further indication that the circumcision question was coming only from a rather narrow group of “fundamentalists.”)

The Church in Jerusalem formally welcomes the delegation from Antioch and in plenary session (apostles and elders are gathered), begin to hear the issues discussed:

The Pharisee party is interested not only in the matter of circumcision, but the larger question of the status of the law in Christian communities: is the whole law binding on Gentile converts as well as Jews?

Much debate arose -- we can only imagine the intensity of the discussions for this question really was at the heart of the Christian self-understanding: is the Church a community of Grace (a new creation) -- or a community of Law (a sub-sect of Judaism)?

Peter, now recently returned to Jerusalem, sees the larger issue clearly and attempts to connect his previous work among Gentiles (Cornelius, Rome etc.) with the present issue. It is not just the case that God has blessed a few Gentiles, but it is the case that God makes no distinctions whatever between Jew and Gentile. And God’s relationship to all is now based on faith, not law. In any cases the law is as impossible for the Jew to observe as it is for the Gentile. Only through grace are any saved -- Jew or Gentile alike.

Now Paul and Barnabas relate their experiences in their missionary effort.

James, the Lord’s brothers now clearly the leader of the Jerusalem community (following James’ death and Peter’s departure) drew the debate to a conclusion by insisting that only a minimal understanding of the Law could be imposed --and those few rules had primarily to do with religious practices.

James, argument carries the day, and the Jerusalem community drafts a letter to be sent to Antioch with an authorized delegation: Judas Barsabbas and Silas (Judas Barsabbas may well be the same man who was nominated to fill Iscariot’s vacancy at the earlier election).

Judas and Silas both prophets (preachers) presented the letter to the Antioch congregation in plenary session. The occasion was one of rejoicing and celebration. The two remained then for an indefinite period of time with the Christians at Antioch, preaching and teaching.

Paul and Barnabas remained at Antioch in their traditional roles, after

Judas and Silas were sent back to Jerusalem.

15-36-41: Paul and Barnabas break company.

After some days, Paul conceived a plan whereby he and Barnabas would retrace their steps through the recently evangelized territories. Barnabas seen-is to have agreed to the plan, but wanted again to take Mark with them. Paul was reluctant; he does not want to take a chance with Mark after his earlier ‘withdrawal’.

The result of this disagreement was a “sharp contention.” Paul and Barnabas now go their separate ways.

How deep was this separation? Not much is known about Paul’s relationship to Barnabas after this separation. But Paul is able to refer to Barnabas with apparent comfort in I Cor 9.6, indicating that there were no lasting ill-feelings.

Paul shows some dissatisfaction -- perhaps disappointment with Barnabas on an occasion shortly after their return from the Council (Gal 2.11-14). Some argue that this was the real reason for the break between Paul and Barnabas not the one which Luke cites here. Unfortunately, little can be said of the nature of the relationship between the two on the basis of this episode.

The word translated “sharp contention” is PAROXYSMOS (paroxysm): it means “irritation.” Paul is “irritated” at the pagans in Athens when he later visits there (17-16) because of their idolatry -- righteous indignation. Paul himself writes in 1 Cor 13.5 that “love is not irritable”, perhaps suggesting that he had learned something from his previous behavior with Barnabas.

It is not to be thought that Paul and Barnabas went away as permanent enemies. The contention that broke out between them was doubtless occasioned by differing expectations about the missionary work and the best working methods to accomplish them. Paul certainly felt he was right, and Barnabas could not work in that way. So the two decided to work independently. We have not the slightest indication that this divergence affected the Christian community adversely or deeply, or that it colored the relationship between the apostles permanently.

Barnabas, perhaps longing for another shot at Cyprus,, headed for his ancestral home with Mark. Paul chose Silas, perhaps not yet departed from Antioch, to accompany him on his return journey.

Silas (the Latin form is Silvanus) was numbered among the “apostles and elders” at Jerusalem (he may have been an apostle: 15-22).

Silas traveled with Paul for some time. Like Paul, he was a Roman citizen, and surely spoke and wrote in Greek. He was imprisoned with Paul in Philippi and was left behind in Berea while Paul went on to Athens. Silas joined Paul in Corinth, and was again left behind by Paul when the latter departed. This may have been his last contact with Paul.

It is conjectured that Silas at some later time went into the regions of Pontus and Cappadocia. Silas, who had known Peter in Jerusalem, may well have been responsible for calling Peter into this area. In any case, Silas appears to have worked with Peter and to have been his amanuensis (scribe) in writing the letters attributed to Peter.