Replica of the Susan Constant and a shallop (small boat).

Map of 1606 route - click to enlarge.

Captain John Smith.

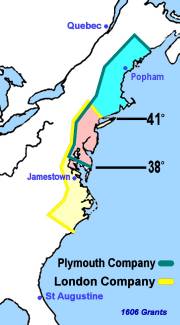

Map showing the division of grants made in 1606..

A Replica of the Mayflower - click to enlarge.

THE TIMES

In 1603, a Queen Elizabeth died and King James VI of Scotland became King James I of England. A terrible plague invaded London. In 1604, the new King authorized the translation of the Bible into English, and scholars from Oxford and Cambridge began their historic undertaking. In late 1605, as Shakespeare was finishing a new play, entitled Macbeth, a certain Guido Fawkes – “Guy” as we know him – organized a plot to blow up Parliament. He wanted to destabilize the government and restore Roman Catholicism. Galileo was writing a book on the supernova, and perfecting something called a proportional compass. He had not yet built a telescope (1609). In 1606, Macbeth opened, Guy Fawkes was executed, and the scholars were still at work. And a group of business men in London began to look to the commercial colonization of the New World. One of them, Bartholomew Gosnold, would not only conceive and launch the plan, but would go on to captain one of the ships that would sail under something called the Virginia Company.

THE VIRGINIA COLONY

The Virginia Company, so called to honor the Virgin Queen (Elizabeth), was issued a Charter by King James on April 10, 1606.

It was, as the charter made clear, organized for three purposes: 1) profit; 2) to find a trade route through Virginia to the Pacific; and 3) to convert the “naturals” or natives to the Christian religion.

The Company acquired three ships, the Susan Constant, the Discovery and the Godspeed. It also recruited some 106 men, among whom were 4 boys, and 39 crew to make the journey. (The exact numbers differ; the figures here are an estimate based on several sources.) The Captain in charge of the fleet was Christopher Newport, a seasoned seaman. The other two ships were captained by Bartholomew Gosnold (Godspeed) and John Ratliffe (Discovery). Newport was 46 years old, and Gosnold, 35 years old. The Susan Constant was the largest of the three, at 120 tons; it was 116 feet in length, about a quarter of that length outside the actual deck. The other two ships were considerably smaller, the Godspeed having a deck size of 52 feet in length and 15 feet wide. The Susan Constant would carry 71 passengers; the Godspeed 51, and the Discovery 20. The conditions aboard these ships were, to say the least, cramped.

The roster of passengers was not promising. A prominent member was Captain John Smith. He was a colorful character who, despite being only about 26 years old at the time of the departure, had already lived an intriguing and adventurous military life. He would become the most famous of the colonists, and would publish the most accounts of the first permanent English colony. Another important member on the roster was the Rev. Robert Hunt, the first Church of England clergyman to go to the New World. But of the rest, half were “gentlemen,” men who thought of themselves as possessing an exalted rank in life and who would not expect, or be expected, to actually do anything, like work!

The ships left London in December, 1606. Almost immediately, the ships and the Company suffered their first trial. The three ships were stalled in the English Channel for several days due to poor winds. This frustrated the passengers to such an extent that many proposed calling off the venture for the time being and postponing the launch until a better time. John Smith and Robert Hunt were apparently the only ones who vigorously opposed this idea, and Hunt played a prominent role in convincing the others to stay the course.

Eventually, the little fleet got underway. They set sail for the Canary Islands in order to take advantage of the prevailing trade winds which, on the eastern side of the Atlantic flow west by southwest. They stopped to take on fresh water for the crossing. They then proceeded to the Caribbean, rounding Martinique on March 23 and putting into Dominica, Nevis, St. Croix, Mona and Monito Islands. They replenished their water and food in each case as was possible and in some instances had some interchange with the “naturals” or natives of the place. They landed on Mona on April 7, and left on April 9. They went to neighboring Monito, the last stop before reaching Virginia. They spent ten days at sea, three days longer than they had anticipated. Again dissension over whether to continue sprang up among the passengers. Commonsense seemed to prevail – after all, it had taken so much time to cross the Atlantic and the prospect of doing it again did not seem inviting. They gave themselves a few more days. Finally, on April 26 they sighted land. They entered Chesapeake Bay and dropped anchor at Cape Henry, so named in honor of one of King James’ sons. It is conjectured that the colonists would have had some sort of celebration – perhaps prayers, perhaps a communion service – but there is no evidence that such was the case.

In the Canaries, John Smith had been accused of “insurrection” and for the duration imprisoned aboard the Susan Constant. When the party finally landed at their destination, the official instructions from the Company in England, which had been placed in a locked box, were taken out and read. The President of the Colony was appointed by the Company in advance, and revealed to be Edward-Maria Wingfield. The Council was also appointed, numbering seven of the men, and included Smith. At this early stage, Smith was not informed of this appointment and remained aboard ship. The instructions also included some very practical advice, notably:

- Take time to find the best site for the base of operations, avoiding marsh lands

- The Discovery would remain with the party for exploration (especially of the supposed passage to the Pacific)

- They were not to offend the “naturals” and should initiate trade with them as soon as possible

The assumption in the instructions was that the colonists would have nothing to fear from the natives, but they were advised that they should be on guard against incursions from the Spanish, or from the Spanish using the “naturals” to effect their own designs. In the event, however, the newly landed colonists were almost immediately involved in a skirmish with some local natives.

Days went by, then weeks, then months with very little accomplished. The critical issues were water, food and shelter. The colonists settled on a peninsula that afforded easy access, due to deep water, to ships. There was plenty of drinking water, at least in the Spring of the year. This would become a problem as Summer went on and the water turned brackish. Wild game was abundant. Berries were available. But there was little else. Eventually, efforts were made to trade for grain among the natives. An initial crop of wheat was sown. But in the matter of shelter, the men lived mostly in tents. A short fence was erected for defense, and would be called “the fort.” It was little more than a barrier or shield. No houses were constructed. Instead, Wingfield wanted to put men to work to make clapboards for sending back on the Susan Constant when Newport returned to England, to demonstrate his commitment to “turning a profit” for the Company. Some exploration took place, principally up the James River. The colonists discovered that the site they had chosen was surrounded by natives who would be or become their enemies. Those tribes who might be considered friendly to their effort tended to be farther away. And, despite the advice in the instructions, the peninsula on which Jamestown was founded, was indeed very marshy – a breeding ground for mosquitoes and all the consequences that go along with them.

Smith was eventually released from captivity and seated on the Council as the instructions had provided. In May, several men, including Smith, went on an extended exploration up river. While they were gone, a band of warriors attacked the settlement. About seventeen colonists were wounded and one of them died later. In addition, one of the boys had been killed. The attackers were warded off by canons from the ships. This attack led the colonists to build a palisade – a stronger defense work – but little else.

Newport left in June. Wingfield was deposed as President and Archer put in his place. As the Summer rolled on, more and more men got sick and fewer and fewer were available for any labor. Ironically, even though malnutrition was taking its toll, few of the men – especially the “gentlemen” – did anything to rectify the situation. In August, about 13 men died from dysentery, or typhoid, or from drinking the brackish water (salt laden). Gosnold was among them.

Smith became an important leader to the community. In December, he went on an expedition to trade with the natives farther away and to bring back much needed grain. A hunting party hostile to the English happened upon him and his men. They captured all of them, and brutally killed all but Smith, whom they discerned to be a man of importance. The warriors and a local chief eventually brought Smith to Powhatan, the “chief of chiefs,” and went through an ordeal. Legend – and Smith himself – says that Powhatan’s daughter, Pocahantas, interceded for the Captain. In any case, Smith emerged as a “subordinate” chief of the tribe and enjoyed good, if not always tenuous, relationships with Powhatan.

Smith would be elected President of the colony in 1608. He ruled with a strong hand, strengthened the defenses and instituted a stern policy of work: “He who does not work does not eat!” The first women, two of them arrived in Virginia in 1608. Smith was injured accidentally in 1609 and was forced to return to England. He never returned to Virginia but promoted the colony in England for the rest of his life (died in 1631).

The following year, 1610, the Virginia Company reorganized itself under a new Charter and gave new powers to the Governor, now virtually a dictator. Thomas West, Lord de la Warr (for whom a river, a bay and eventually a colony would be named - "Delaware") became Governor. Although intended to attract more colonists and make the colony profitable, these changes had the opposite effect. Colonists continued to come, but they also continued to die. About this time, 1612, John Rolfe (who had married Pocahontas) hit upon a new strain of tobacco. This opened the way to developing a cash commodity for lucrative export. Many of the farmers began to grow tobacco. This was so successful, they devoted their energies to the cash crop and failed to plant food crops. In 1618, the Company changed policies again. Sir Edwyn Sandys (son of the Archbishop and member of Parliament), the Company’s London treasurer, set up offers of tracts of land to those who would go to Virginia and work. This became very attractive and the Colony grew steadily. The Company also authorized an Assembly to govern the colony and make its own rules. In 1619, the Assembly declared the Anglican Church to be the Church in Virginia. There were then about 5 clergy and 3,000 residents. In 1619 for the first time a Dutch ship came to Jamestown carrying African slaves. Slave labor had already been instituted in the Caribbean by the Portuguese for sugar plantations. By the end of the century, slave labor would be important in Virginia as well, and lead to its eventual success.

Trouble with the natives continued. In 1622 the colony came under native attack. Nearly a quarter of the colonists died – 347 of them. This came to be known as the Indian Massacre. Soon after this, the Virginia Company’s charter was revoked and the Colony came under the authority of the Crown. The policy of the Crown was very harsh toward the remaining Powhatan tribe. It is estimated that the tribe numbered 25,000 in 1607. That number fell to a few thousand by 1630. A final attack came about in 1644, and the ageing chief was jailed. The Powhatan dominance in Virginia ended.

THE PLYMOUTH COLONY

At about the time the Virginia Colony was finally getting on its feet, another group of adventurers put together a plan for establishing a colony.

At the time the Charter for the Virginia Company was issued in 1606, the charter envisioned two separate but related entities. The first would be called the Virginia Company of London, and the second the Virginia Company of Plymouth. The first granted the settlement of land in the South and the second granted the settlement of the land in the North. The areas overlapped and the overlap area (in pink) was subject to special rules.

In 1607 a colony was established in Maine, called Popham. But it collapsed in 1608. The northern area, therefore, lay fallow for the years after 1608. It was, however, well known to many Europeans – some of whom had explored the area (Capt John Smith had named the area “New England” when he visited and surveyed it in 1614). Fishermen were familiar with the waters and may have contributed to the spread of small pox and other diseases among some of the natives.

A group of separatists who would come to be known as “Pilgrims” meanwhile left England (Scrooby in Nottinghamshire) for the Netherlands in 1609. Seeking to escape what they felt as persecution for their religious views, they settled first in Amsterdam and then in Leiden.

They were free to worship and assemble as they wished in this Protestant stronghold. But they in time grew concerned as their children were picking up Dutch culture and language. They determined to find a way to move to the New World, aided by contacts who had remained in England, largely in hiding. They obtained a land patent in 1619 to settle at the mouth of the Hudson River, and a group of Puritans known as the Merchant Adventurers put together the money to finance the trip. A ship, the Speedwell, brought the Pilgrims to England to meet up with the Mayflower, take on board the needed supplies and the passengers and proceed to New England.

Joining the Pilgrims were another group, including Myles Standish, collectively know as the Strangers. This group was not characterized by the same religious motivation that marked the Pilgrims; they were a various lot who possessed skills or experience the Adventurers thought necessary to the success of the colony.

The whole group on two ships was intended to set sail in July, 1620. But disputes and issues concerning organization and funding delayed the launch until August 15. When they finally got underway, the Speedwell began to leak and the fleet had to return to England. The Speedwell was determined to be un-seaworthy, and some of the passengers abandoned the effort. ( It is believed the crew sabotaged the ship in order to get out of the extension of their contract.) The rest were bundled aboard the Mayflower, which got underway on September 6, 1620.

Although the exact dimensions of this ship are unknown, it is likely to have been about 180 tons, with a length of around 100 feet, and a width of 25 feet. Typically, it would have a crew of between 25 and 30 men. There were on board a total of 102 souls as passengers in addition to the crew. The ship was captained by Christopher Jones.

Unlike the ships going to Virginia, Jones decided to risk a direct crossing, no doubt due to the late time in the year. So it is not surprising that the arrival of the Mayflower off the North American coast was much farther north than was intended. It anchored in what is now called Provincetown Harbor, at the tip of Cape Cod, on Saturday, November 11, 1620. The passengers remained aboard on Sunday, for worship.

Immediately, the recognition that they were much farther away from their intended destination raised problems. There was no authority to create a settlement here. While aboard ship, the famous Mayflower Compact was created – a kind of charter for the new community. While having no authority in its own right, and was very similar to traditional English town charters, it seemed to remove a pint of anxiety for most of those on board.

For the next many days, while living aboard the cramped quarters, some of the men undertook several exploratory expeditions. Finding no place suitable for a settlement, the ship set out again and anchored in Plymouth Harbor, across from the tip of Cape Cod, on December 17. They explored the area for their settlement. They rejected several, but selected an abandoned native site, Patuxet, which had two hills. (The natives had died of smallpox not long before the arrival of the English.) They would locate the village on the one, and place a canon for defense on the other. The compelling factor of this site was that it had been cleared by its former inhabitants, making the planting of crops much easier.

Astonishingly, many of the passengers remained aboard the ship, many for as many as six months! Some work began on the building of shelters, but the weather made a concerted effort difficult. Through the first winter only seven houses and four “common houses” were built, and all were very simple, rudimentary structures. Many of the laborers, and the women and children, were weakened by malnutrition or died of disease. Only 51 colonists survived the first few months.

The Plymouth colony had many encounters with their native neighbors. Eventually, the colonists were able to forge a relationship with the leading sachem, or chieftain, of the Wampanoag confederacy of tribes. Massasoit, the great sachem, looked to an alliance with the English to protect his tribes from their enemies, the Narragansett. Massasoit is credited with helping to preserve the colony from starvation in its earliest stages. Ninety of Massasoit’s warriors celebrated with the 51 surviving colonists at a harvest feast in 1621.

The next colonists to arrive, 37 of them, came in November of 1621, and this was greeted with joy and relief. (Among them, one Philip de la Noye; his name eventually changed to Delano, and one of his descendants was Franklin Delano Roosevelt.) A further 90 or so settlers arrived in 1623. By 1630, the colony had 300 residents. In 1692, when the colony was absorbed into the Massachusetts Bay Colony, it had about 3050 residents. The whole of New England was incorporated into something called the Dominion in 1686 and included Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, New Hampshire and the Jerseys (East & West). It had a President who was very unpopular, however, and Plymouth returned to self rule. In 1691, following the accession of William of Orange (and the overthrow of James II), Plymouth was included in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

At first, the colonists found fur trade to be economically beneficial. They also tried fishing, but found that they had little or no skill in this and abandoned the effort. With the arrival of cattle around 1627, and subsequently pigs and sheep, their economy became more diversified. The Plymouth colony also benefitted from trade with the natives and with the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. After the first rocky years, the colony became largely self-sustaining.

The relations between the Plymouth colony with the native Americans, like that in Virginia, was mixed and complicated. Myles Standish early on led a sharp and deadly attack on unsuspecting native neighbors. This unfortunate event colored English-native relations for years to come with suspicion and intrigues. As noted, it was the determination of Massasoit, however, that assured the survival of the colonists in the first tenuous months and years, unfortunately to the detriment of his own people.

COMPARISONS OF THE TWO FIRST PERMANENT COLONIES

SIMILARITIES

1. Both colonies were established by men (and in the case of Plymouth, women) who were ill equipped to undertake such a mission. There was no preparation for the journey, and little capacity among the passengers for dealing with the basic challenge: the bringing into being of a community that was self-sustaining.

2. Both colonies lacked sufficient support, especially in terms of military aid and training. Virginia had its Captain John Smith, and Plymouth its Myles Standish. Smith had a somewhat broader military experience than Standish and both were quite self-confident, indeed boastful about their abilities. It is interesting to note that John Smith had actually applied to be the military advisor for the Plymouth colony, but despite his experience was turned down in favor of Standish. In any case, besides these two, neither group had seasoned, experienced or capable military men to assist in advising and preparing the colonists for self-defense.

3. In both cases, the colonists themselves were slow to sense the perils around them, even including the hardships presented by the weather, and neither showed any great exertion to build a stable and secure community. In both cases, it would be months before their settlements would even begin to take shape.

4. Both colonies suffered greatly from disease made worse by malnutrition. Surprisingly, no provision had been made for a physician to accompany them. What remedies they could find often came from the practices of the native peoples.

5. With respect to the native population, both groups shared certain basic assumptions which would become problematic:

a. The English regard for “naturals” differed from the Spanish. The Spanish typically saw the natives of a land as less intelligent, indeed less than human, and fair game for subjugation. Interestingly, the English understood “savagery” as a lower rung in social development rather than in racial terms. ���Savages could not rightfully be enslaved.” In fact, the English settlers actually thought that the natives of North America were “white” men, since their babies were born “white.” They thought the “red” in "redmen" was due to the habit of painting – the incessant use of dyes on their bodies. The English understood themselves to have been once “savages” until the arrival and civilizing influence of the Romans. So they saw their efforts in North America, as it were, in this light.

b. The colonists were hampered by inadequate information about the native populations in their respective areas. No one seems to have known of the numbers of tribes and the size of populations, let alone of the languages, cultures, organization and level of sophistication among the tribes. Both colonies had been encouraged by their backers in England – indeed expected – to begin trade with the native peoples where possible. But with their presuppositions concerning the “primitive” state of affairs among the tribes, no one thought to gather significant information about these often complex societies. Some, John Smith among them, actually tried to acquire some of the native languages and to understand the social structures and relationships. But these efforts were pretty minimal.

DIFFERENCES

1. The primary difference between these colonies lay in the motives behind the founding of each.

a. The Virginia Colony was a business enterprise, intended to turn a profit for its investors. Some of the colonists were “gentlemen” who had actually themselves invested in the project.

b. The Plymouth Colony was envisioned as a religious community where Puritan Separatists could be free to practice their religion without interference of the State. This vision drove the Pilgrim colonists even though they, too, were expected to make a return on the investments of their backers.

2. The southern colony would be a bastion of Anglicanism from the beginning; the northern colony a bastion of Calvinist theology and all the tensions that went with the differences in emphasis between competing groups (Separatist Puritans and non-Separatist Puritans-Congregationalists).

3. The northern colony right from the start was characterized by settled families; the southern colony by male adventurers.