Ministry to Native Americans:

In the colonial period, there seems to have been a genuine interest in ministry to native tribes. But language and custom barriers, and mutual suspicion – not to mention occasional outbreaks of war – limited success.

There was a school for Indians established at College of William and Mary in Virginia, but it was not notably successful and was closed after the revolution.

In Western New York, there was more success – even a Mohawk version of the BCP. Under Bishop Hobart, special work was begun with the Oneida Indians and met with success. Hobart was a popular person among the Oneidas. Hobart appointed Eleazar Williams as a missionary to them – he was of mixed native/white parentage. Williams in turn led a group to Green Bay, Wisconsin where another church was established.

James L. Breck established a mission to the Chippewas in Minnesota, in the 1850s. Henry B. Whipple was consecrated in 1860 as Bishop of Minnesota and immediately sought to expand ministry to the native Americans. Whipple was a key figure in the government’s dealings with Indians, chairing the commission that met with the Sioux following the massacre of Custer’s army. One of his first ordinations was that of Samuel D. Hinman who carried on an extensive mission to the Sioux and translated the BCP into Dakota. Whipple and William Welsh (chair of the Congressional Board of Indian Commissioners) formed the Indian Commission of the Church’s Board of Mission. They chose William Hobart Hare (grandson of John Henry Hobart) missionary Bishop of Niobrara, which eventually encompassed all of South Dakota. His task was to christianize the native Americans of the Great Plains.

By the turn of the century, Bishop Hare had confirmed some 7000 native Americans.

Bishop Peter Trimble Rowe (consecrated 1895) organized and extended ministry to the Eskimos of Alaska as that area's first bishop. He was assisted by Archdeacon Hudson Stuck. Rowe died in 1942, serving as bishop for 47 years!

The first native American bishop was Harold S. Jones, Suffragan of South Dakota (1971-1976).

William C. Wantland (Seminole), Steven T. Plummer (Navajo), Steven Charleston (Choctaw), are modern bishops of Native American descent.

William Augustus Muhlenberg

W. A. Muhlenberg was born in Philadelphia in 1796 to German

Lutheran family.

W. A. Muhlenberg was born in Philadelphia in 1796 to German

Lutheran family.

- Brought into the Church by Jackson Kemper as a teen.

- Educated at University of PA and studied theology with Bps. Wm. White and Kemper

- 1817: Ordained deacon

- Muhlenberg was always innovating, particularly with respect to education and music – wrote many hymns

- Established the Flushing Institute in New York – a great exemplar of Muhlenberg’s principles and an influential center of learning.

- Established St. Paul’s College in 1838 – chapel being the central and most important part of a disciplined community life he envisioned.

- He traveled to England, especially Oxford, and established many important contacts – e.g., J. H. Newman

- At fifty years of age, he planted a new Church, exercising complete freedom in shaping its life – Church of the Holy Communion – characterized by: daily morning and evening prayer, separated MP, Litany and Communion, weekly Holy Communion, systematic offerings for the poor, special emphasis on Holy Week, boys choir.

- Muhlenberg helped immensely to demonstrate what a parish could and should do.

- Described himself as an Evangelical Catholic – a published a journal by that name.

- Established St, Luke’s Hospital

- Established the Sisterhood of the Holy Communion – a community of women that was more like a school of deaconesses than a religious order

- In his 70s, he established what he called St. John-land – a planned community for the working class.

- Energetic, yet tender and kind; innovative, but not faddish; a dreamer, but also a doer who accomplished great and lasting projects.

(For more writings of Muhlenberg, see Project Canterbury)

The Muhlenberg Memorial: (click here to read it)

1853: a group of clergy headed by Muhlenberg petitioned the House of Bishops to consider ordaining clergy who would not necessarily serve the Episcopal Church or belong to ECUSA.

The impulse seemed to be that ECUSA should bear responsibility for the general provision of spiritual care for the nation – it was a first expression of ecumenical spirit.

It also included provisions for the relaxation of requirements for the deaconate and far greater liturgical freedom, and greater emphasis on intelligent preaching (education).

There were many problems with the Memorial, and not any of its central recommendations were accepted. But General Convention did permit greater flexibility in liturgy, giving greater freedom to clergy; it established a commission on Christian Unity, but it did little.

It also had indirect effects on future Prayer Book revision. (M. Shepherd)

CIVIL WAR

Facts:

- Works of charity have always been an interest and concern of the Church

- But there was no policy of positive engagement with social reordering – indeed, there was a strong presumption against such a policy

- Between 1789 and 1830, there was a general low regard for the institution of slavery – most people in the society, both in the South as well as the North believing that the institution would disappear – that it was transitional

- In 1808 the Congress passed a law banning the importation of slaves

- By 1830, however, cotton had become a giant industry: in 1795, just over 5 million pounds of cotton was being produced annually; by 1830, over 300 million pounds were produced annually.

- In 1820, cotton constituted 22% of the nation’s exports in 1860, cotton constituted 57% of the nation’s exports

- What made the difference was the invention of the cotton gin in 1792, and its expansive use in the south.

- Slavery had become vital as an economic factor due to the lack of ready labor in the South

- Two movements sharpened the divide between North and South

in this period:

a) In the South, and from some in the North, a “humane” interpretation of slavery

b) In the North, and in some places in the South, a movement for Abolition

The Churches on Slavery:

- Quakers were the first religious body in the US to condemn slavery, but were so small as to not influence in any real degree public opinion.

- Methodists forbade members to be slaveholders – modified its stance with respect to laity on clergy, sharp confrontation on opinion in 1845 a convention of the churches in the South formed a new Church.

- Baptists were congregational in polity, but united in associations. In 1845, the Southern Baptist Convention was established, largely based on southern support of slavery.

- Presbyterians – a more complicated situation – resulted in two splits: in 1857, “New School” Presbyterians divided in the North and the South over attitudes toward slavery; the Northern "New Schoolers" opposed and banned slavery, while those in the South tolerated it. The "Old School did not split until the Civil War, and again they split on geographical lines.

Episcopal Church on Slavery:

Never split on the matter of Slavery - 5 reasons:

- a) “secular affairs” were no proper concern of the Church

- b) Sympathies and friendships among Northern and Southern Church members; indeed, many of the Church’s leaders were related by marriage;

- c) Pragmatic – it was difficult to see how the issue of slavery, even if abolished, could be dealt with in a coherent fashion – there were simply too many – this was a failure of imagination and ability

- d) Dread of schism – fear that division in the political realm would be multiplied by division in the Church

- e) LEAST CREDITABLE: the fact is that in the south the wealthiest and most influential social as well as religious leaders were Episcopalian – a split would have deep consequences for the mission of the whole.

Record on Slavery:

- Bishop Whittingham of MD declared slavery a great social evil

- Bishop Alonzo Potter decried slavery in response to a book by a fellow Bishop

- The Rev. E. M. P. Wells of Boston was vice president of the American Anti-Slavery Society

- Lay people like William Seward and Salmon Chase were active in the Republican party and openly opposed to slavery

-

Bishop Hopkins of Vermont, and Dr. Samuel Seabury, Rector of

Church of the Annunciation in Boston – Northerners, be it noted,

defended the institution of slavery on the grounds of “love of

neighbor”(!)

a) The institution was not condemned in the Bible

b) It placed new burdens on Christians to educate, care for and shape these benighted souls in love.

Division of the Church:

- Political secession preceded and led to the division within the Church

- In the South, the notion was – very Anglican – that the Church should be a national Church

- Since the Confederate States now constituted a new nation, the Church should respond to this political situation

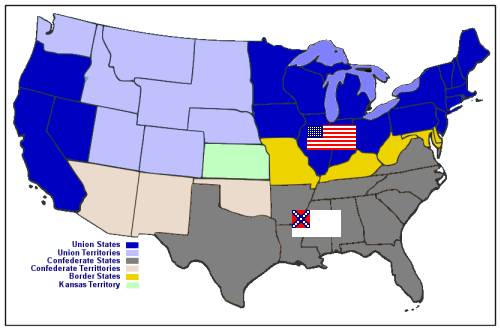

- 1860, December 20: SC seceded;

- Six weeks later, joined by MS, FL, AL, LA, GA, TX.

- 1861, Feb 4: Confederate States of America was formed

- 1861, Apr: NC, VA, AR, TN joined the CSA

- 1861, July 3: A preliminary meeting was held in Montgomery to explore putting together a southern church

- 1861, Oct 16: 10 of 11 bishops, 19 clergy, 14 laymen adopted a new constitution, canons and prayer book for the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America

- 1862, Sep 19: Bishop Elliott of GA announced that the Constitution had been ratified by the requisite 7 dioceses – this just 3 days before the Emancipation Proclamation.

- 1862, Nov 12: The First General Council of the new Church met.

The Episcopal Church during the War Years:

- In late September of 1862, the General Convention of the Episcopal Church met in New York

- There was a strong move to condemn the leaders of the church in the South for “sins of rebellion, sedition, and schism” – this was rebuffed

- There was an equally strong move to distance the Church from any statement concerning what was viewed as merely civil affairs

- The Convention determined to speak up, however, about their

support of the Union. The result was a Resolution:

a) renewing its prayers for the President and the civil authority

b) alluded to the “deep and grievous wrong” which the actions of the South “inflicted” on the Church - Despite this action, the roll call of the deputies and bishops proceeded to include the Southern States even though none of them were in attendance, expressing a sense, if only symbolically, that the Church was not split and would eventually find healing.

- Bishop Hopkins – his sympathies with the South well-known – became Presiding Bishop at the General Convention of 1865. This went a long way toward reconciliation, just six months after the surrender at Appomattox.

- Hopkins issued a warm invitation to his brother bishops to return and assured them that they would be “cordially received.”

- Southern Bishops reacted differently:

a)Bishops Gregg of Texas and Atkinson of NC were in favor of reunion

b) Bp Davis of SC was opposed

c) Bp Elliott thought they could not return until their own Convention had acted.

d) Bp Atkinson attended, as did Bp Lay, who had been made Diocesan of Ark; at the General Convention Arkansas was considered a Missionary Diocese, and Lay as a Missionary Bishop.

e) General Convention also ratified the consecration of Wilmer as Bp of Alabama, which had occurred in the interim - 1865, Nov 8: The second General Council of the PECCSA took action to free the member dioceses to reunite with the PECUSA since the political circumstances had changed. Within a year all the dioceses had transferred to PECUSA.

Growth:

- In 1866 the Episcopal Church, all dioceses considered, had grown to 160,000 communicants.

- In 1870, the Episcopal Church ranked 6th among Church bodies in the US, the Methodists being 1, Baptists 2, Presbyterians 3, and the Roman Catholics being 4. The ratio was 1 Episcopalian to 209 – about ½ of 1 percent.